Build a WebAssembly Language for Fun and Profit: Parsing

Drew Youngwerth

August 25, 2022

In the last post of this series on how to build a WebAssembly programming language, we constructed a lexer. In this post, we’ll cover the next phase of our compiler, parsing. Parsing is the portion of our compiler that takes the token stream generated by the lexer and converts it into an abstract syntax tree (AST).

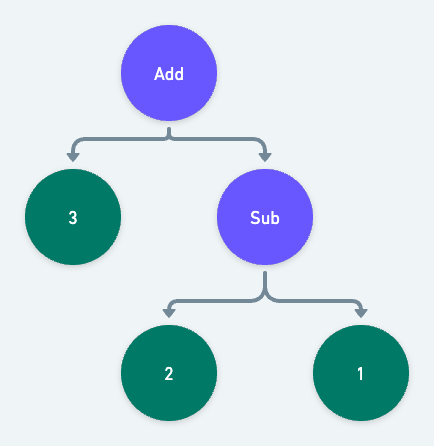

An AST is a tree-like data structure that organizes the tokens into a logical hierarchy that can more easily be translated into machine code. Thankfully, because wispy is an S-expression language, our code is essentially already an AST. Take the following stream of tokens:

Copied!

“(“, “add”, “3”, “(“, “sub”, “2”, “1”, “)”, “)”

Each set of parentheses represents a subtree, where the first token is the operator node and the following tokens are its operands. If we run into another opening parenthesis before the current set is closed, we know it represents an operand that itself is a subtree. The above stream of tokens would be organized into a tree that looks like this:

If you're interested in writing a parser for a more complex C-like syntax, see my previous Building A Programming Language series.

More About AST

As we did with the lexer, we'll start by defining our types. These types will define the structure of our AST. Each type represents a “Node”, the circle from our diagram in the intro. Here are the basic nodes. We'll gloss over them, as they aren't a lot different from the tokens we defined in the lexer:

Copied!

// src/types/ast.mtsexport type IntNode = {type: "int";value: number;};export type FloatNode = {type: "float";value: number;};export type IdentifierNode = {type: "identifier";identifier: string;};export type TypedIdentifierNode = {type: "typed-identifier";// Note that here, we break down the identifier into its componentsidentifier: string;typeIdentifier: string;};

A new concept to the AST is the BlockNode. A BlockNode is an expression made up

of a group of other nodes.

For example, (add 1 2) is a block of three nodes:

- An identifier that evaluates to a function,

add. - An Int that simply evaluates to the number

1. - An Int that simply evaluates to the number

2.

How the block itself gets evaluated is up to the compiler. We'll get to that in the next post.

Here's the definition:

Copied!

// src/types/ast.mtsexport type BlockNode = {type: "block";expressions: AstNode[];};

Finally, we define the AstNode. Like the Token type from the lexer, AstNode is a discriminated union that can be one of any other node we previously defined:

Copied!

export type AstNode = IntNode | FloatNode | IdentifierNode | TypedIdentifierNode | BlockNode;

You may have noticed that BlockNode has an array of AstNodes, Since AstNode can be a BlockNode, BlockNodes can contain child BlockNodes. In other words, BlockNode is a recursive type. This ability to recursively represent children that can have children is the foundation of our AST. It's where the tree in AST is allowed to form.

At this point src/types/ast.mts is finished and should look like this file.

Now export the types from src/types/index.mts as we did with the token types:

Copied!

// src/types/index.mtsexport * from "./token.mjs";export * from "./ast.mjs";

Constructing the AST

Now that we've defined the AST, it's time to build one.

Create a new src/parser.mts file and add all the imports we'll use:

Copied!

// src/parser.mtsimport {Token,IdentifierNode,TypedIdentifierNode,IdentifierToken,TypedIdentifierToken,FloatToken,FloatNode,IntToken,IntNode,AstNode,BlockNode,} from "./types/index.mjs";

Now we can define our top level parse function. The parse function takes the tokens

generated by the lexer and returns a BlockNode that acts as our tree’s root.

Copied!

// src/parser.mtsexport const parse = (tokens: Token[]): BlockNode => {const blocks: BlockNode[] = [];// This loop is run as long as there are tokens to consumewhile (tokens.length) {// consumeTokenTree converts an array of tokens into a tree of tokens, more on that later.const tree = consumeTokenTree(tokens);// parseBlock turns our new tree of tokens into an actual BlockNode, recursively. More on that later as well.blocks.push(parseBlock(tree));}// Finally we return the top level BlockNodereturn {type: "block",expressions: blocks,};};

Next we define the consumeTokenTree function. consumeTokenTree converts a flat array of tokens, into a tree of tokens.

Given this wispy expression:

Copied!

(add (sub 3 1) (sub 5 2))

The lexer will produce this array of tokens:

Copied!

// Note: I've simplified the Token format to just be strings to keep things short["(", "add", "(", "sub", "3", "1", ")", "(", "sub", "5", "2", ")", ")"];

consumeTokenTree will take that flat array and turn it into a tree. This is as simple

as putting every token in between a set of bracket tokens () into an array. So our

token array from above becomes this token tree:

Copied!

["add", [, "sub", "3", "1"], ["sub", "5", "2"]];

Here's the actual definition of consumeTokenTree:

Copied!

// src/parser.mts// This is token besides for the bracket tokensexport type NonBracketToken = Exclude<Token, "parenthesis" | "square-bracket">;// The token tree is made of NonBracketTokens and other TokenTreesexport type TokenTree = (NonBracketToken | TokenTree)[];const consumeTokenTree = (tokens: Token[]): TokenTree => {const tree: TokenTree = [];// Ensures the first token is a left bracket and then discards it, defined below this function.consumeLeftBracket(tokens);while (tokens.length) {// Preview the next tokenconst token = tokens[0];// Check to see if the next token is a left bracket.if (token.type === "bracket" && getBracketDirection(token) === "left") {// If it is, we just ran into a sub-TokenTree. So we can simply call this function within// itself. Gotta love recursion.tree.push(consumeTokenTree(tokens));continue;}// Check to see if the next token is a right bracketif (token.type === "bracket" && getBracketDirection(token) === "right") {// If it is, we just found the end of the tree on our current leveltree.shift(); // Discard the right bracketbreak; // Break the loop}// If the token isn't a bracket, it can simply be added to the tree on this leveltree.push(token);// Consume / discard the token from the main tokens arraytokens.shift();}// Return the tree. Don't forget to check out the helper functions below!return tree;};const consumeLeftBracket = (tokens: Token[]) => {const bracketDirection = getBracketDirection(tokens[0]);if (bracketDirection !== "left") {throw new Error("Expected left bracket");}return tokens.shift();};const getBracketDirection = (token: Token): "left" | "right" => {if (token.type !== "bracket") {throw new Error(`Expected bracket, got ${token.type}`);}// If we match a left bracket return leftif (/[\(\[]/.test(token.value)) return "left";// Otherwise return rightreturn "right";};

Now that we have a token tree, we need to turn it into a block. To do so, we create a

parseBlock function that takes the tree as its input and returns a BlockNode:

Copied!

const parseBlock = (block?: TokenTree): BlockNode => {return {type: "block",// This is where the recursive magic happensexpressions: block.map(parseExpression),};};

As you may have noticed, parseBlock maps each item of the tree with a yet to be written

parseExpression function. parseExpression takes either a TokenTree or a NonBracketToken and transforms it to its corresponding AstNode type.

Here's the definition:

Copied!

const parseExpression = (expression?: TokenTree | NonBracketToken): AstNode => {// If the expression is an Array, we were passed another TokenTree, so we can// pass the expression back to the parseBlock functionif (expression instanceof Array) {return parseBlock(expression);}// The mapping here is pretty straight forward. Match the token type and pass the// expression on to a more specific expression parser.if (isTokenType(expression, "identifier")) return parseIdentifier(expression);if (isTokenType(expression, "typed-identifier")) return parseTypedIdentifier(expression);if (isTokenType(expression, "float")) return parseFloatToken(expression);if (isTokenType(expression, "int")) return parseIntToken(expression);throw new Error(`Unrecognized expression ${JSON.stringify(expression)}`);};

Let's define the isTokenType function. This function is pretty neat and demonstrates

one of the most powerful features of TypeScript, custom type guards. Simply put, isTokenType tests the expression and narrows down the type to a specific TokenType. This allows TypeScript to be certain we are passing the correct tokens to their corresponding parser functions down the line.

Here's the definition:

Copied!

export const isTokenType = <T extends Token["type"]>(item: TokenTree | NonBracketToken | undefined,type: T): item is Extract<Token, { type: T }> => {return isToken(item) && item.type === type;};const isToken = (item?: TokenTree | NonBracketToken): item is NonBracketToken => {return !(item instanceof Array);};

There's a lot happening there, so let's walk through it. First up, we have a generic definition,

<T extends Token["type"]>. This is essentially saying that T must be one of the possible values

of the Token.type field. Typescript is smart enough to know that means T must be one

of "int" | "float" | "identifier" | "typed-identifier" | "bracket.

The next interesting piece of code is the return type predicate item is Extract<Token, { type: T }>. This predicate tells TypeScript that if the return value of isTokenType is true, then item must be the Token whose type matches the string passed as the type parameter.

In practice that means that if we were to pass an unknown Token to isTokenType, typescript

will be able to correctly narrow the value to a more specific token, like IntToken.

Now that we have our custom type guard defined, we can define the actual token parsers. The first three are simple; they essentially just return a copy or slightly modified copy of the token:

Copied!

const parseFloatToken = (float: FloatToken): FloatNode => ({ ...float });const parseIntToken = (int: IntToken): IntNode => ({ ...int });const parseIdentifier = (identifier: IdentifierToken): IdentifierNode => {return {type: "identifier",identifier: identifier.value,};};

The final parser is the parseTypedIdentifier. Remember that a typed identifier takes the form

identifier:type. Parsing it is as simple as splitting the string by the colon. The first value

of the returned array is the identifier, the second is the type.

Here's the definition:

Copied!

const parseTypedIdentifier = (identifier: TypedIdentifierToken): TypedIdentifierNode => {const vals = identifier.value.split(":");return {type: "typed-identifier",identifier: vals[0],typeIdentifier: vals[1],};};

That's all the code required for a working parser. Before we move on, let's update the main

src/index.mts file to view the output of the parser:

Copied!

// src/index.mts#!/usr/bin/env nodeimport { readFileSync } from "fs";import { lex } from "./lexer.mjs";import { parse } from "./parser.mjs";const file = process.argv[2];const input = readFileSync(file, "utf8");const tokens = lex(input);const ast = parse(tokens);console.log(JSON.stringify(tokens, undefined, 2));

Build and run project:

Copied!

npx tscwispy example.wispy

If all goes well, the output should look like this.

With that, the parser is finished. We can now convert the stream of tokens from the lexer into an AST. In the next post, we can get into the juicy bits: generating and running machine-readable code.

Similar resources

Expo Push Notifications: The Complete Implementation Guide (SDK 52+)

Expo push notifications are alerts sent from a server to a user's phone, even when the app isn't open. To set them up, install the expo-notifications library, ask the user for permission, and get a unique push token for their device. Your server sends a message to Expo's push service with that token, and Expo delivers it through Apple or Google. Push notifications only work on real phones, not simulators. Local notifications are different — they're scheduled by the app itself for things like reminders. You can also route Expo push through services like Courier to add email, SMS, and Slack fallbacks.

By Kyle Seyler

February 24, 2026

Best Email API Providers for Developers in 2026: SendGrid vs Postmark vs Mailgun vs SES vs Resend

Your email provider sticks with you longer than most technical decisions. Courier handles notification infrastructure for thousands of teams, so we went deep on the six email providers that show up most: SendGrid, Postmark, Mailgun, Amazon SES, Resend, and SMTP. This guide covers real API primitives, actual code from each provider's docs, Courier integration examples with provider overrides, and an honest read on where each developer experience holds up and where it breaks down. We also asked Claude to review every API and tell us which one it would wire up first. The answer surprised us.

By Kyle Seyler

February 23, 2026

The Courier MCP Server Is Open Source. Here's How It Actually Works.

Courier's MCP server is open source at github.com/trycourier/courier-mcp. It connects AI coding tools like Cursor and Claude Code to your Courier account so they can send messages, manage users, and install SDKs without hallucinating API details. This post walks through the actual codebase: how 16 tool classes are registered (and how a config allowlist gates most of them), why we pull installation guides from GitHub at runtime instead of bundling them, how the DocsTools class generates live JWTs alongside setup instructions, and what the SdkContextTools class does in the repo to prevent v7/v8 SDK conflicts (even though it isn't wired into the server yet).

By Mike Miller

February 06, 2026

© 2026 Courier. All rights reserved.